Personal Victories in a Safe House for Women in Peru

In July, Partners In Health established the first safe house for women living with schizophrenia in Lima.

Posted on Nov 20, 2015

No one would say a hospital psychiatric ward is a cozy place to call home. Yet in Peru, many patients who have been stabilized after a schizophrenia diagnosis have no choice but to remain institutionalized, largely because they have nowhere to go and lack the skills they need to live independently.

Valeria Ruiz* was one such patient. In October 2014, the 21-year-old was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and obsessive compulsive disorder and admitted to a hospital in Lima, Peru’s capital. By July, she no longer required hospitalization, but her mother—who also was hospitalized for mental illness—was in no shape to take care of her. Her father had abandoned her long ago.

Thanks to a new program sponsored by Socios En Salud, as Partners In Health is called in Peru, Ruiz moved to a safe house for women diagnosed with schizophrenia. She lives there with seven other women who are medically stable, but who have been socially abandoned. Community health supervisors teach Ruiz and other residents how to perform everyday activities, interact with each other, and navigate the outside world with the hope of someday living independently.

PIH’s safe house is the first of its kind in Lima and could serve as an example for other countries facing a similar dilemma. According to the World Health Organization, mental disorders account for 14 percent of the global burden of disease. Most of the people affected—75 percent of whom live in low- and middle-income countries—do not have access to the treatment they need.

That's about to change. Several years ago, Peru's Ministry of health began tackling the nation's mental health care gap—or the number of people who need services, but can't access them. Ministry staff turned for advice to the World Health Organization, which had published a guide in 2010 that helps countries weave mental health care into the services offered by neighborhood clinics, the ground floor of the health care system.

In Peru, most mental health care takes place in three hospitals in Lima. Primary care doctors tackle a range of diseases, but often aren’t trained to identify mental disorders, such as depression and schizophrenia. Up until recently, they also weren’t allowed to prescribe psychotropic medication. This means most patients seeking mental health services receive inadequate care, or none at all.

While the ministry revamped its approach to mental health care, Congress passed key legislation to push along the issue. The law now states that mental health is a basic right, and that primary care physicians can prescribe psychotropic drugs.

All this was in motion when Jerome Galea, deputy director of PIH in Peru, and Giuseppe (Bepi) Raviola, PIH’s cross-site mental health team leader, met with Peru’s mental health coordinator early last year. They were on a mission. They’d seen how patients living with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis or HIV struggled with depression and psychotic side effects from grueling drug regimens. While they knew PIH support groups had helped patients manage for decades, they wanted a more sustainable solution.

“To our great surprise, we learned that Peru was right on the cusp of a national level of implementing mental health services at a primary care level,” Galea says. “The stars aligned.”

In early 2015, the ministry began training Lima’s primary care physicians and nurses to identify mental disorders so patients can be properly diagnosed and receive care in any one of the capital’s 350 primary care clinics. That was the first step. The next involves extending the same coverage to all of Peru’s 7,000 community clinics. Outpatient community health centers will also be established as specialized facilities for patients who need a higher level of care, but do not require hospitalization.

The ministry requested Galea and Raviola’s help in one area: They didn’t know what to do with chronically ill patients who were ready to transition from hospitals to homes. These women and men—who likely number in the thousands, if they were all identified and treated throughout the country—no longer required the intensive (and expensive) care of a hospital. Yet they couldn’t function as adults capable of completing household tasks or holding down a job.

'We need hundreds of these houses, not one, and that’s part of the plan'

The ministry had a solution, but needed PIH’s help to carry it out. In June, PIH opened Lima’s first safe house, or hogar protegido, for women living with schizophrenia. Peru’s National Institute of Mental Health chose four women from those in its care, aged 18 to 65, to be the home’s first residents. Four more women have since moved in. It’s a small step, but everyone involved is carefully measuring the house’s success with an eye to further expansion.

“We need hundreds of these houses, not one, and that’s part of the plan,” Galea says. “We’re writing the manual of operation, the recipe, and will help the Ministry of Health duplicate it and scale up.”

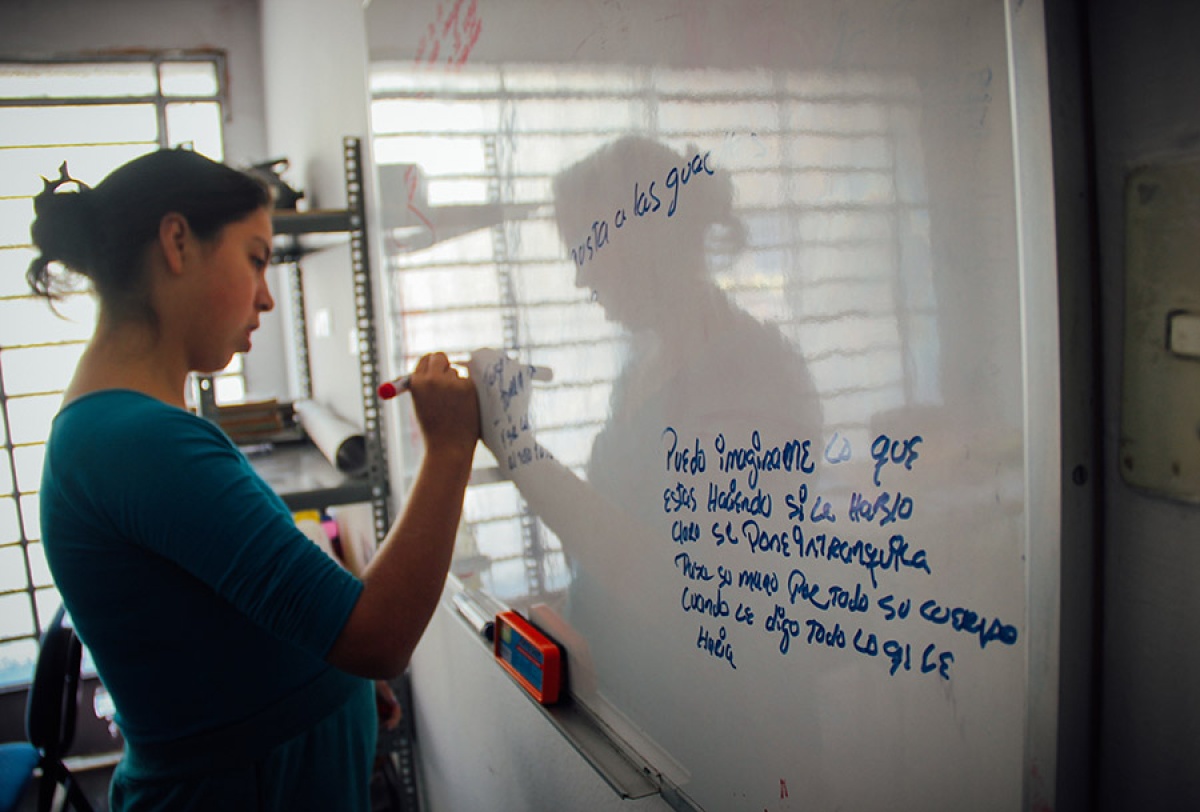

Six community health supervisors take shifts so the safe house has 24-hour supervision. They teach the women how to complete basic household chores—such as clean, make a bed, and do laundry. Together they go on errands around the neighborhood. They buy bread. They go to the library. And they attend community classes to acquire new skills to enter the work force. While these accomplishments seem small, they are significant.

Rosa Cadena has seen the women grow in their new environment. "My job is to guide them," the supervisor says, "to try to help the women return to a normal life."

One resident has shown marked improvement. When she arrived, she hardly spoke and wouldn't unpack her bags or sit on furniture. Now she helps with chores, sings, and doesn't shy away from a friendly touch.

The supervisors “don’t just make sure residents take their medication,” says Kelly Tamo, a psychologist and PIH’s mental health coordinator in Peru. “Their role facilitates the transition to life outside of a hospital.”

Ruiz, too, has blossomed. She says she feels “more lucid, more normal” since moving into the safe house. There’s a childlike quality, an earnestness about her. Her face is without expression, her voice flat, as she shares her personal victories: bathing herself, cleaning her bedroom, going to church on Sundays.

Someday Ruiz hopes to take classes toward a career. But for now, she’s content transforming empty toilet paper rolls into elaborately designed pencil holders, which she sells in a nearby market. She takes money she earns to her mother, whom she still visits in the hospital.

“When I was a little girl, I learned how to make them from a T.V. show,” she says. “I’ve been practicing ever since.”

*Name has been changed