Study Brings Relief to Rwandans with Hepatitis C

Posted on Apr 27, 2017

Dr. Shumbusho gazes intently at her patients from behind narrow glasses, her gray wisps of hair pulled back into a bun, and listens to them describe the challenges of their deteriorating health. They have come to Rwanda Military Hospital from across the country, seeking answers about hepatitis C, an illness that causes ongoing damage to their livers.

Some didn't know they had the disease until recently. Others did but haven’t been able to do anything about it, because treatment has long been difficult to access. Hepatitis C drugs are expensive, don’t always work, and come with severe side effects. But if the disease is left untreated, up to 20 percent of these individuals will develop liver cirrhosis. Up to five percent of them will die of liver cirrhosis or liver cancer.

The good news is that the latest hepatitis C drug, approved in 2014, is almost 100 percent effective and carries only typical side effects you’d see on any drug label. The bad news is it was originally priced at more than $1,000 per pill, which is taken every day for 12 weeks.

Paying this price isn’t an option for Shumbusho’s patients, whose annual income is less than $700 a year. But in this hospital, there are closets full of the medication because these patients are part of a clinical study Shumbusho and her colleagues are leading to understand who contracts hepatitis C and how they respond to treatment.

“The true burden and impact of hepatitis C in sub-Saharan Africa has never been quantified,” explains Dr. Neil Gupta, a former chief medical officer for Partners In Health in Rwanda and a principal investigator of the study. Nobody really knows how many people have the disease in Rwanda, especially in rural areas, he says, but the government estimates as many as 55,000 have advanced hepatitis C. Why the prevalence is so high and how people contract it is unclear.

That’s why Rwanda Military Hospital, the University of Rwanda, the Rwanda Biomedical Center, Stanford University, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Partners In Health established the study, which will identify and treat 300 participants over two years. Most of them are subsistence farmers and rural residents who otherwise would have no way of being treated.

Shumbusho has seen patients every day since February. They arrive—many of them after very long journeys—get their bloodwork done, and receive the medication. Then fatigue shifts to relief. For many, it’s the first time they’ve received treatment for an illness that has plagued them for decades.

Their gratitude spurs Shumbusho on. “It’s very motivating.”

|

|

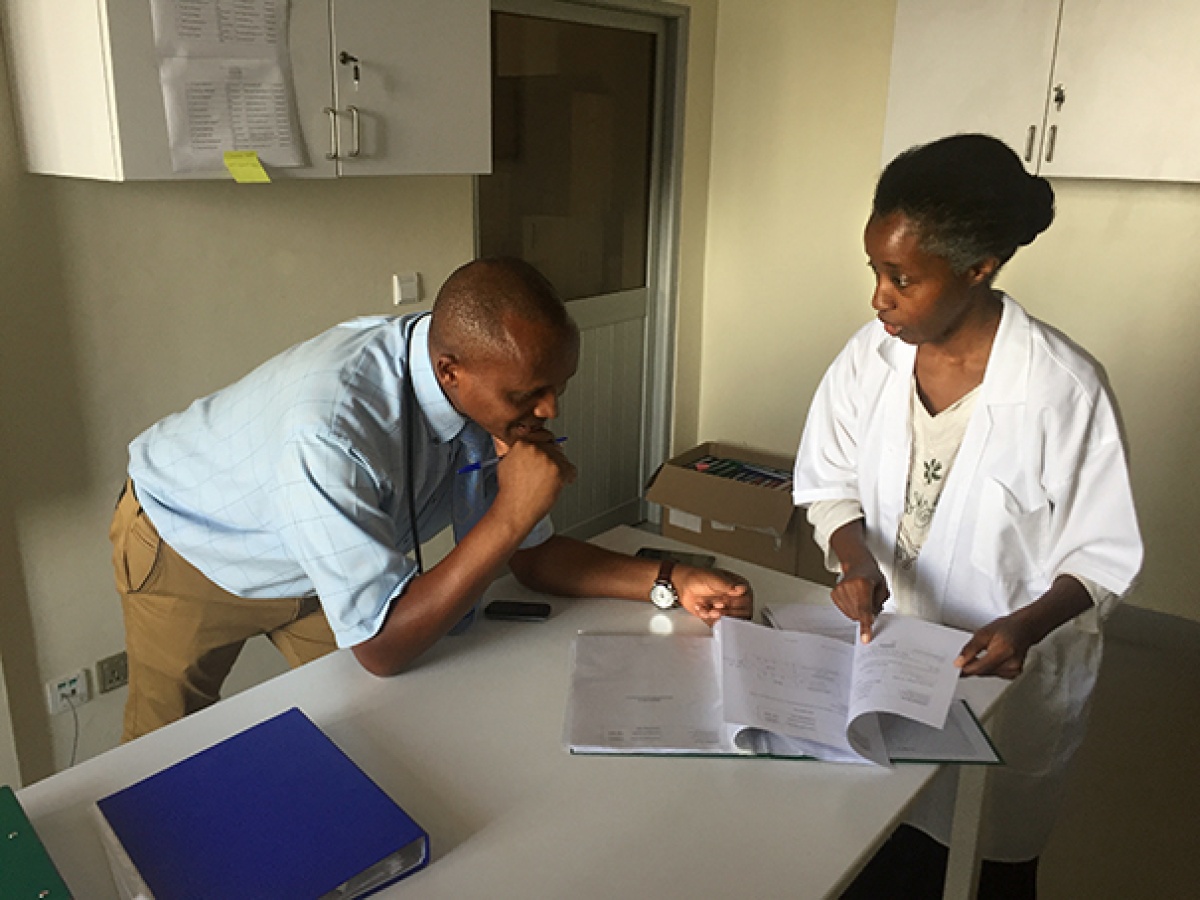

Study Coordinator Alphonsine Imanishimwe counsels a new patient through her first dose of medication. Photo by Neil Gupta / Partners In Health |

Patients come back every month for three months so Shumbusho can monitor their progress. She’ll keep track of their weight, hear how they’re coping with the daily medication, monitor any side effects, and log these details for the study.

By late 2017, Shumbusho, Gupta, and their colleagues will not only have a sense of why the disease is so prevalent and among whom, but they’ll also provide recommendations for improving treatment policies around it, such as how many blood tests patients should receive and how often they should see their doctors.

Rwanda Military Hospital will be further set up to handle hepatitis C in the future. It will have a pharmacy stocked with drugs, clinicians trained in the specifics of the disease, and a new machine for diagnosing hepatitis C.

And they’ll have hard evidence that treatment with the right drugs is a surefire solution. Gupta hopes the study will get more attention on the topic and stimulate research. “We need more work like this,” he says.

Most importantly, the study will cure hundreds of very sick people. For Gupta, access to treatment is the main goal. “The drugs are extremely effective and are not reaching the majority of people who need them,” he says. “Our ultimate objective would be to use this experience to demonstrate and advocate for access to this treatment for millions of others in resource-poor settings globally."

Gupta and other authors recently published a baseline study for hepatitis C treatment in Rwanda.

|

|

J.M.V. Halleluia is a laboratory technician working on the study. Photo by Aaron Levenson / Partners In Health |