The Drum Major Instinct: A Reflection on Martin Luther King Day

Posted on Jan 9, 2014

Editor’s note: To celebrate Martin Luther King Day, we’re re-reading Dr. Paul Farmer’s 2009 speech at Boston University, Dr. King’s alma mater. Published in his 2013 book, To Repair the World, Farmer reflects on King’s final speech about the “drum major instinct.”

The Drum Major Instinct: Reflections on Dr. Martin Luther King, Leadership, and the Challenges Still Before Us

By Paul Farmer

Speech delivered at Boston University, 19 January 2009

1. I have a dream

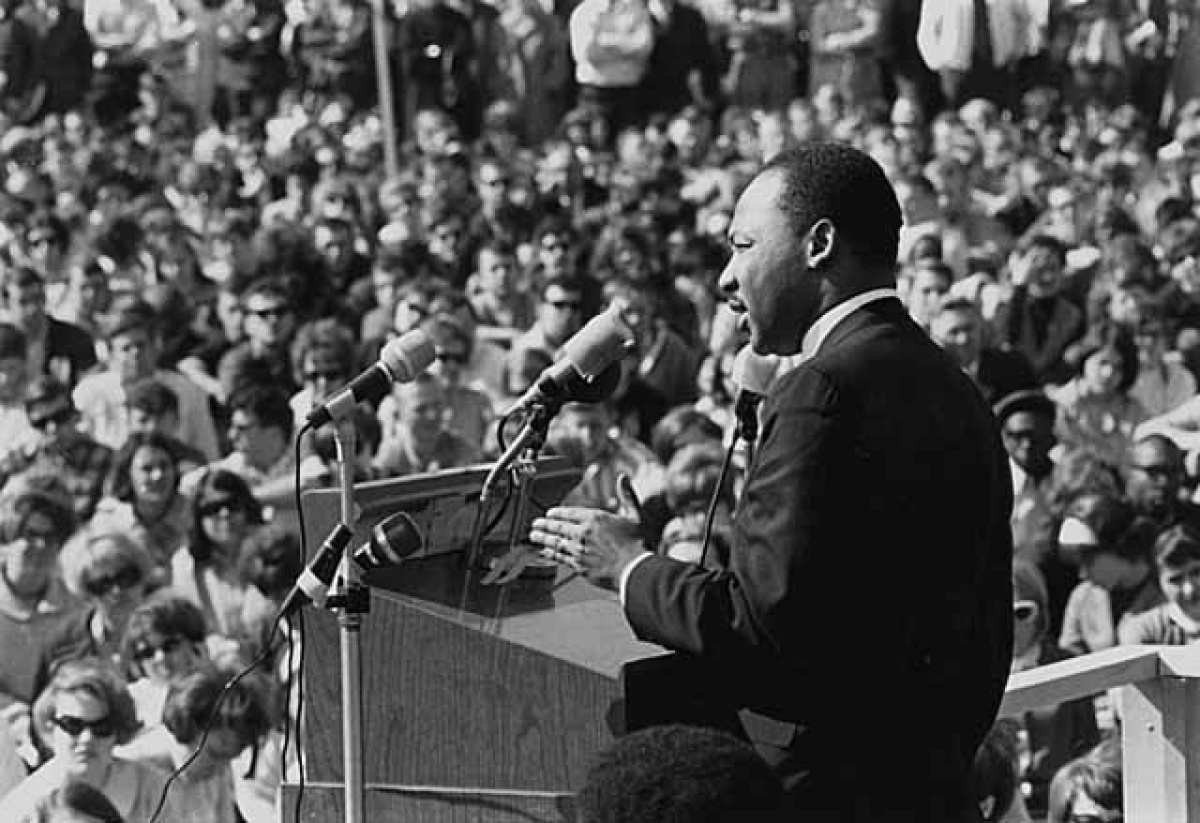

Everybody knows Dr. Martin Luther King’s four most famous words. They were spoken during his 1963 speech on the Mall in Washington. It’s an event that is on a lot of people’s minds these days because of another event that is shortly to take place in Washington and which might be taken to confirm the ability of majority Americans, after decades of being pushed, educated, and transformed, to judge each other “not … by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

In particular, he had his eye on the treacherous point where the quest for excellence and for personal efficacy compromises the broader goals of equality and justice for all.

Today I’ve been invited to reflect on another of Dr. King’s sermons, less well known than the “I have a dream” speech, but one with a message for this week and this moment in our country’s history. I am honored to make these comments at Dr. King’s alma mater, on the day people across the world honor his memory. I am grateful to draw on his work, which continually inspires my own, and to use it to reflect on the challenges now before us. And although my remarks will engage the worldwide struggle to reach our full promise as humans, with rights inalienable in principle but far from obtained, I will not be coy about their meaning for Americans on the eve of the inauguration of President Barack Obama.

It is fitting that this year’s MLK celebration has blurred into our inauguration of a new president. I’ll bet we’ll hear references tomorrow not only to Lincoln but also to King. Both have much to teach us, both fit on that arc of history that bends, however slowly, towards justice. And as Lincoln’s brooding marble image presides over the proceedings, so too will MLK’s rhetoric of dreams suffuse our hearts, today and tomorrow.

The dream described in the 1963 speech on the National Mall was about equality. “The Drum Major Instinct,” Dr. King’s last sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church, in 1968, is about leadership. Don’t these two speeches seem to head in opposite directions: equality being for all of us, leadership a role only a few of us can play? But as Dr. King analyzes it, what he calls the “Drum Major Instinct” is the desire, most likely innate in all of us, for the praise and recognition that come with leadership. Who doesn’t fantasize about being in charge, whether as drum major in a marching band or as leader of a movement or head of a department or, even, as president of a flawed but promising democracy? These roles gratify our hunger for applause and approval. But King also saw the darker side of leadership. He spoke rawly and honestly about the dangers inherent in “keeping up with the Joneses” and of striving to impress through material advantage. In particular, he had his eye on the treacherous point where the quest for excellence and for personal efficacy compromises the broader goals of equality and justice for all.

What do all of us, with our potential for leading and for following, have to offer in a struggle that may echo the past, but is necessarily the present, and thus new?

Dr. King is now an American icon. But we can’t forget that he was a controversial figure in his time—controversial even among his supporters, who couldn’t always see where he was going or how the parts of his program fit together. If it was difficult, for some people in 1968, to understand the complexity of King’s reflections on theology, or on the struggle of poor people in far-off Vietnam, it can’t be so difficult for any of us, for all of us, to see how the greater good might be damaged by one person’s overweening efforts to be the best, to lead. We recognize ourselves in the straw man of the “Drum Major Instinct.” There’s a reason, surely, that Coretta Scott King asked that this sermon be replayed at his funeral. For in this homily, Dr. King, Nobel laureate and hero to millions, refers presciently to his own funeral and asks that no mention of his many awards and honors be made. Let it only be said, he asked, that he strove to “feed the hungry,” to “clothe the naked,” to “be right on the [Vietnam] war question,” and to “love and serve humanity.”

To feed the hungry, clothe the naked, stand up for peace, and love and serve humanity: These issues, transcendent today, are central to any ideas a doctor might have regarding, say, the right to health. They are precisely the priorities that should guide public policy and private action in times of economic turmoil. How do we accomplish these aims without making them serve our own love of glory and admiration? How do we, gathered here today, on January 19th, 2009, at Boston University, fit into a plan larger than ourselves, a plan that might move us beyond our own ineradicable Drum Major Instinct without dampening our desire to succeed? What do all of us, with our potential for leading and for following, have to offer in a struggle that may echo the past, but is necessarily the present, and thus new?

If MLK were with us today, in flesh and not (as he is) in spirit, he would surely be pleased by the events that will unfold tomorrow in our nation’s capital. But he would not regard this momentous event, the inauguration, as the end of the struggle, but as an opening, a chance, a space in which a much broader social-justice agenda might be pursued. In making this claim, I do not also claim to know King personally. I was eight years old when he was taken from us. But all of us can know his mind through his speeches, sermons, and actions. And these can leave us little doubt about his views on justice, views which would not be vindicated by Barack Obama’s gaining high office unless that office were used to pursue a more just vision of our nation and our world. Likewise, there’s little doubt about Dr. King’s views on the wars conducted on the basis of lies: simply speaking out, even from a position of power, against such wars will not suffice.

If MLK had a dream towards the end of his life, it was the dream of a much more radical equity. It is for this reason that he has never faded away, as have many other noble people martyred for their just beliefs. MLK’s mature dreams, those laid out with clarity in the last months of his life, are precisely those we need to inspire us in a time of great need.

2. Dream or nightmare?

In a celebration like this one, and in a time like ours (fraught with promise and peril), it’s possible to forget the hard work still before all of us. Yes, we stand on the shoulders of giants and yes, it was harder then, when the civil rights movement as we know it was played out in this country. I may have been only eight when Dr. King was killed, but I lived in Birmingham at the time and I bring my own interpretive grid to a modern reading of his works and life. In “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” he famously noted that “we will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people.” Just as it was the silence of good people that permitted some of the excesses of recent years—and for me these excesses include not only the war in Iraq but also the overthrow, yet again, of democracy in Haiti and also our appalling silence on the right to health care in our own country—it is also the collective roar of good people that promises to redress them. Many of you will agree: we are even today filling appalling silences with a loud and optimistic chorus of commitment to doing better. Certainly, I hear the loud roar of the students!

The ghost of white supremacy continues to fade, here as elsewhere. But the all-encompassing struggle for social justice is in some ways in its infancy.

We know, of course, that good intentions are not sufficient to do the job, any more than is reluctant compliance with progress. After leaving the tumult of Alabama shortly after King’s death, I still remember waiting, with my five brothers and sisters, for the school bus in a small Florida town. Jim Crow had been struck down legally, perhaps, but at the gas station that was our bus stop were two bathrooms. They were labeled “Men” and “Women,” but above these labels were, still readable, the ghostly shadows of the five letters that had been painted over not too long before. The image sticks in my mind as much as the grainy, black-and-white-photographs of MLK in D.C.

The stain of Jim Crow, itself the legacy of slavery, will, like the fates meted out to Native Americans, be with us always. But what is the message in such dramatic changes as we have seen since MLK made the ultimate sacrifice? Or even since 1992, when the theologian James Cone wrote a book called Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare? In it, Cone asked not so much how far we’ve come, but rather how the visions of MLK and Malcolm X came together towards the end. Both were fighting, in their own ways, for a vision of social justice. MLK embraced a Gandhian perspective on this struggle, and was criticized for it by some in the movement. In many ways, he has been vindicated. Malcolm was less ready to limit the struggle to nonviolent resistance, and his legacy has been more mixed, but it would be incorrect to deny him credit as a motivator of social change. The difference between the conditions that brought MLK to the Mall in the sixties and that will bring Barack Obama to the Mall tomorrow is patent, and deserves to be celebrated—and we should do so on both of these days.

The ghost of white supremacy continues to fade, here as elsewhere. But the all-encompassing struggle for social justice is in some ways in its infancy. MLK understood this, especially towards the end of his life, as clearly as anyone.

3. Human rights and social justice

In some ways, King is like other iconic leaders, especially those martyred, a screen against which we can project our hopes and aspirations. The same has been said about our president-elect, and that’s a heavy burden to carry. Let’s take King, not as an icon, but as a work in progress. Take him in those years between 1963 and 1968. He was moving forward on his own intellectual and moral and political path, learning about the world. After all, there was MLK the seminarian and MLK the doctoral student at BU and MLK the preacher and MLK the national leader and MLK the Nobel laureate and MLK of the poor people’s movement. He was, as they say, all that. He knew what he was talking about when he warned against the drum-major instinct. He was changing and growing and learning all the time, and guarding against any tendency in himself to take credit, to take charge, to treat a social movement as his personal accessory.

We need to acknowledge that he was working towards a goal, which was the fight for social justice for all, a fight against poverty.

In celebrating Dr. King, we need to respect his own trajectory and growth, not just the final form of a name, a postage stamp, a monument, a chapter in the history books. We need to acknowledge that he was working towards a goal, which was the fight for social justice for all, a fight against poverty. “The curse of poverty has no justification in our age,” he wrote in 1967. “The time has come for us to civilize ourselves by the total, direct and immediate abolition of poverty.”

As in his final sermon, he spoke of the hungry, the naked, the homeless, the thirsty, the vulnerable. Elsewhere, he spoke explicitly of health disparities, and in a way that no doctor should fail to appreciate. “Of all the forms of inequality,” he said, “injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.” Will this form of inequality be addressed in our lifetimes? And he took on the great controversies of the day. Here’s what he said about the Vietnam War: “The bombs in Vietnam explode at home; they destroy the hopes and possibilities for a decent America.” He opposed the war for several reasons, but perhaps the most important ones were that he regarded the justification for the war as fraudulent: “We are adding cynicism to the process of death, for they [US troops in Vietnam] must know after a short period there that none of the things we claim to be fighting for are really involved. Before long they must know that their government has sent them into a struggle among Vietnamese, and the more sophisticated surely realize that we are on the side of the wealthy, and the secure, while we create a hell for the poor.”

MLK also believed the resources spent on war should be spent on the war on poverty. He argued that “a nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.” In expressing these views, King was not seeking to win a popularity contest. A significant fraction of the mainstream media, journals that had previously praised King, voiced their opposition to his opposition. Life magazine termed the speech in which these words were uttered “demagogic slander that sounded like a script for Radio Hanoi.” The Washington Post opined that he had “diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, his people.” The Drum Major Instinct, if not held in check, might well have led King to accept postures more palatable to the mainstream media, the newspapers, magazines and television programs that had celebrated him in previous years.

Here’s what he said about hunger: “I started thinking about the fact that we spend millions of dollars a day to store surplus food in our country. And I said to myself, "I know where we can store that food free of charge: in the wrinkled stomachs of the millions of God’s children in Asia and Africa, in South America, and in our own nation, who go to bed hungry tonight.”

This is not ancient history. Don’t we, here today, still need to deplore unjust wars? The bombing of civilian populations? Don’t we still need to think about social justice? About hunger that causes food riots in cities across the globe? Don’t we need, in the midst of financial crisis, to reflect on King’s argument that “true compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar . . . [True compassion] comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring”?

4. Accepting our need to celebrate

It would be possible to end these remarks in a scolding or otherwise negative tone. I might have reminded all of you that Dr. King was willing to die for his convictions, did not shrink from danger, and faced death bravely and calmly. I might have insisted that because we still confront injustice, and even racial injustice, we have made no or too little progress. I might have underlined only what is wrong and failed to signal what it right and promising and new.

I do not choose to do that today.

Today we celebrate the life and legacy of Martin Luther King. Today we celebrate his courage and his paradoxical relationship to the drum-major instinct. Without that instinct, he would not have pursued either his career or his vocation. Had he lacked it, he would not have gone to jail, nor would he have spoken to millions, directly and with courage. But Dr. King was aware of the risks of seeking to elevate himself above others, and it is for this reason, among others, that he sought to ground himself in the struggles of the poor in this country and elsewhere. It is for this reason that he never became a gaudy and flashy “brand,” to use the language of our day.

The greatest thing about King’s redemptive vision is that all of us may, at any time, choose to place the well-being of others above our own.

Let us all take inspiration from a man who, years after receiving a Nobel prize, would seek to learn and to grow, a man willing to take on conventional wisdom, even when it rankled some of his supporters and many of his fair-weather friends.

And finally, let us celebrate the optimism of MLK. He never failed to believe in the promise of our species. Fallible humanity was his inspiration every bit as much as his God. Redemption is always possible. “We must accept finite disappointment,” he cautioned, “but never lose infinite hope.”

Finally, we need to acknowledge the drum-major instinct within all of us, the urge to be somebody and to succeed. If not for that impulse, who among us would be here today, at one of the great universities of this country? I know I would not be here as a physician and teacher. Barack Obama would not be our nation’s 44th president. But the greatest thing about King’s redemptive vision is that all of us may, at any time, choose to place the well-being of others above our own. All of us may strive for compassion, justice, and altruism. None of us need have the vision, talent and heroism of an MLK to succeed in this humble and necessary task. “Everybody can be great,” said Dr. King, “because anybody can serve.”

Now, as our country and our world faces financial crisis, environmental disaster, war, and growing inequality, is the time to serve. It’s a great time to serve a just cause, to concern ourselves with the oppressed or those less fortunate. It’s a great time to do what many BU students have done: to draw on deep reserves of compassion and solidarity and, above all, to engage. If this is what we do with our Drum Major Instinct, we need not be troubled by it. Everybody can be great, because anybody can serve. Thank you all.

[Originally published January 2009]

Read many other reflections by Dr. Farmer in his book, To Repair the World.